European red foxes (fox, Vulpes vulpes) are a serious vertebrate pest and are listed in the World Conservation Union’s list of the 100 worst invasive species (PDF 1.3MB).

Since their introduction in the 1850s, foxes have spread across almost 80% of Australia and are now widespread in most environments except for some islands, fenced refuges, and the far tropical north. Recent estimations of Australia’s fox population are around 1.7 million.

Foxes pose a threat to wildlife and livestock through predation and the spread of disease. In high-density areas, they may also be a health risk to humans and pets in the same ways.

Foxes eat many things (mostly live prey, carrion and insects, but also fruits and berries) and have few natural enemies or serious diseases in Australia. It is estimated that foxes eat 370–530 g of food a day, rising to 1113 g for lactating females.

Foxes are generally nocturnal, making it difficult to estimate their numbers. Both males and females reach sexual maturity at one year of age. Breeding occurs once a year in winter, and litters of 3 to 6 cubs are born in spring. Young foxes disperse in late summer or autumn.

Quick breeding means populations recover quickly from challenges like drought or too-infrequent control programs.

Foxes have defined home ranges, but travel for seasonal food. Dispersing young foxes cover significant distances, with females averaging about 14 km and males 68 km, but they have been recorded travelling up to 300 kilometres.

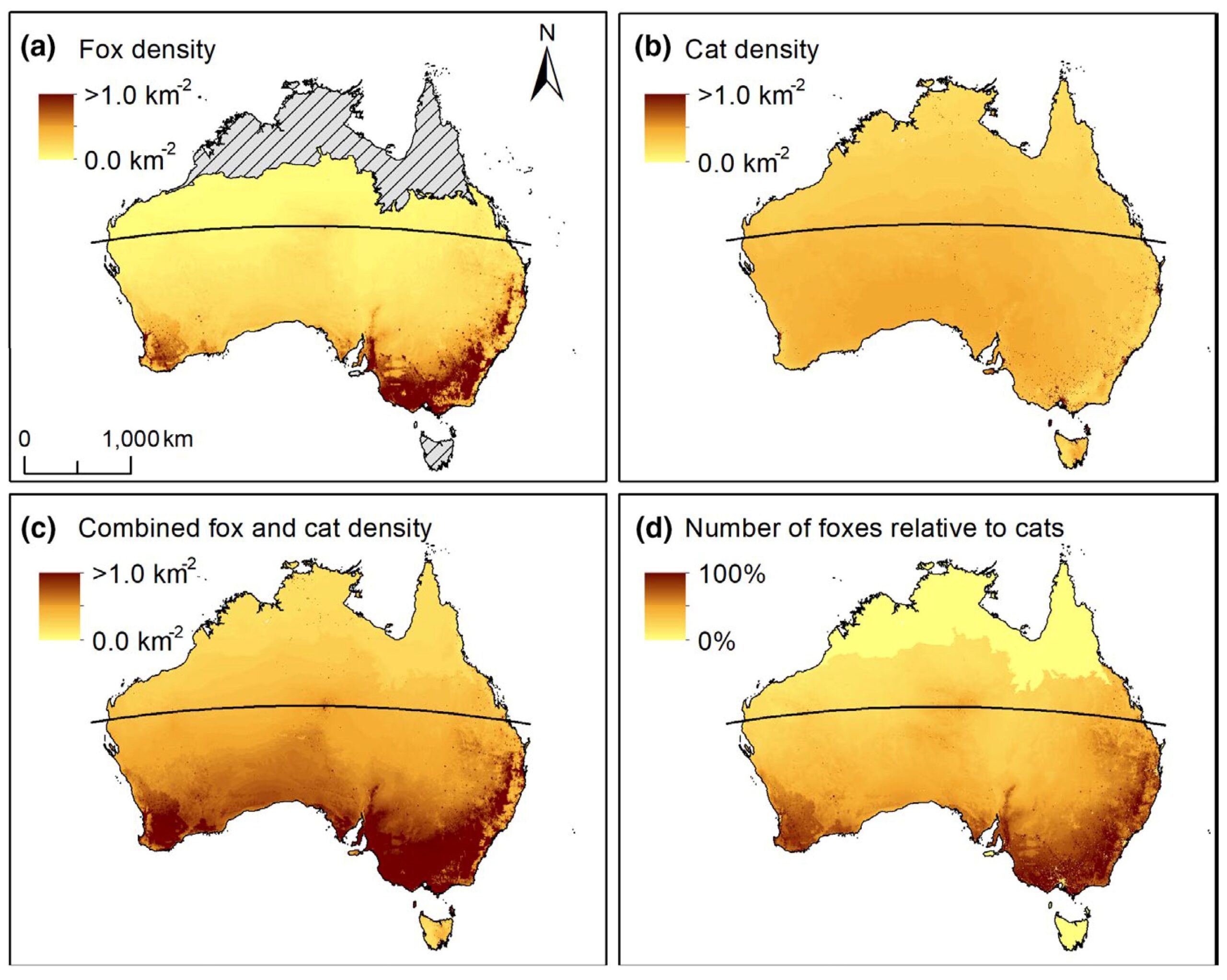

Density estimates vary widely across their range and can change in response to rainfall and the availability of in food.

The highest densities are found in urban areas (e.g. 16 per km2 in urban Melbourne) and in temperate areas of southern mainland Australia (e.g. 4–8 per km² in temperate agricultural areas); there are lower densities in warmer and tropical regions (e.g. to less than 2 per km2 in most semi-arid grazing areas).

Foxes pose a significant threat to native wildlife and livestock. Photo: Mary Anne Addington.

The modelled density of foxes and cats (including pet cats) throughout Australia. The solid black line indicates the Tropic of Capricorn. Source: Stobo-Wilson et al. (2022).

Impact of foxes

Foxes are one of the most damaging invasive animal species to native wildlife in the country. Foxes impact wildlife and livestock through predation, competition and the spread of disease. Estimated costs of foxes to agriculture based on private landholder responses to the 2019 ABARES landholder pest and weed management survey was $198 million, $147 million in private control costs and $51 million in residual agricultural losses. Estimating biodiversity costs in dollars is very hard to calculate; however, some reports have indicated it could be as high as agricultural costs.

By controlling fox populations, it is possible to reduce these impacts.

Agricultural impact

Foxes kill and injure livestock, transmit diseases such as hydatids, distemper, parvovirus and mange, spread weeds and damage infrastructure.

Predation has the biggest impact, particularly to lambs, kid goats and poultry. Foxes are known to kill more than they eat, leading to more livestock deaths than the fox population size suggests. The average predation of foxes on lambs is estimated to be 7%. In certain areas, foxes can cause the loss of 10–30% of lambs (PDF, 1.4 MB) and possibly more. When in high densities, foxes might also contribute to mismothering of lambs by ewes.

Fox predation on livestock has an annual economic cost of more than $198 million.

However, this estimate does not include damage to infrastructure, the spread of weeds, time lost to fox control, or the health and agricultural cost of transmission of diseases. The wider costs of foxes to agriculture in Australia are yet to be accurately estimated.

Biodiversity impact

In Australia, at least 33 mammal species, excluding subspecies, have become extinct since European settlement. This is the highest rate of mammal extinctions in the world.

Foxes have played a key role in the extinction of at least 14 native mammals and one native bird species – including the crescent nail-tail wallaby, lesser bilby, desert rat-kangaroo, desert bandicoot, desert bettong, lesser stick-nest rat, two species of hare-wallabies and the paradise parrot.

Foxes also significantly contribute to the ongoing decline of many Australian animals. They are a key threat to more than 95 nationally threatened species (620 KB), such as the malleefowl, bridled nail-tail wallaby and night parrot.

Despite rabbits being a favoured food in many areas, native mammals appear in fox diets more commonly than reptiles, birds or introduced mammals, highlighting the devastating impact foxes have on our native species. More than half a billion reptiles, birds and mammals are eaten by foxes each year in Australia.

How vulnerable a native species is to fox predation is highly variable, some species can co-exist with foxes, others cannot. Many threatened mammals cannot survive even with low densities of foxes. Those that are extremely fox-susceptible are now found only in small areas (islands and mainland fenced enclosures) where foxes are absent. Identifying where native species fall along this continuum is critical for shaping the fox management actions necessary to prevent declines and extinctions.

Foxes also prey on and compete with native predators, such as quolls. For example, there is significant overlap between the diet, habitat and den sites of foxes and spotted-tailed quolls (Dasyurus maculatus).

Foxes and feral cats hunt similar sized animals. This predation pressure has caused the extinction or population declines of a number of native species. However, the interactions between these two predators are complex and not always predictable. As an example, their predation pressure on some susceptible prey species is likely greater than the sum of their two parts but for other, less susceptible species, this is not the case. Strategic and targeted programs that manage predation of both invasive predators are likely to yield the best results.

Predation by foxes and feral cats combined, take a huge toll on native wildlife. Estimated number of animals killed in Australia each year by feral cats and foxes using an estimate average feral cat or fox density of 1 per 4 km2. Source: Stobo-Wilson et al. (2022). Note: feral cat and fox densities, and therefore their predation impacts, vary with different habitats and food availability.

Social impact

The main social impacts of red foxes are not direct impacts, but rather flow out of the economic and environmental impacts. However, some direct social impacts can occur. Examples include psychological distress caused by fox predation on household pets, poultry and livestock, and trauma from vehicle accidents.

Many native species hunted by foxes and cats have important cultural significance to First Nations people’s stories, knowledge, food and health of Country.

Foxes carry diseases such as mange, hydatid tapeworm, leptospirosis, canine distemper, canine parvovirus, encephalitis and rabies (not yet found in Australia), which can be transmitted to native species, humans and/or livestock. For example:

- Hydatid worms are found in canids (such as foxes and dogs), and if the eggs are ingested by people they can cause cysts in various organs, including the brain.

- Leptospirosis, common in north-eastern New South Wales and Queensland, can be spread from animals to humans though contaminated water, soil or infected animals. Symptoms in people can be mild (fever, headache, vomiting and diarrhoea) to severe (organ failure, breathing difficulties, heart disease) and can result in death.

In urban areas, where fox numbers are highest, they harass and kill pets and poultry, dig up gardens and lawns, get into rubbish and compost, defecate in gardens and chew on infrastructure such as garden hoses and irrigation systems.

Foxes impact ground-nesting species like malleefowl (shown here) and turtles by digging up nests and eating eggs and young. Photo: Tony Buckmaster.

Do you have foxes?

According to a recent national survey, 54% of landholders reported a problem with foxes, which is not surprising given that foxes are found in 76% of Australia (ABARES 2022).

However, livestock losses or other problems might also be from wild dogs or dingoes, feral cats or pigs. So working out if foxes are the cause of your loss or impact is important. You need to rule out other predators.

As foxes mostly hunt at night and are elusive, directly observing them killing animals can be difficult. You will probably need to rely on other signs.

As well as the indicators of foxes listed below, the Glovebox guide for managing foxes (PDF, 1.1 MB) and Planning guide for fox management in Australia (PDF 933KB) can help determine if you have a fox problem.

Indicators of foxes

- Seen or heard in your area. Where you see one fox, there are likely to be more.

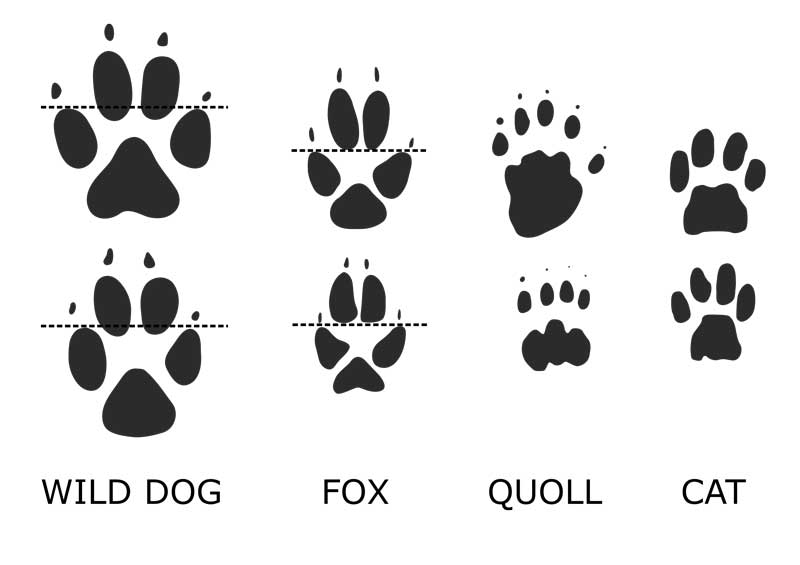

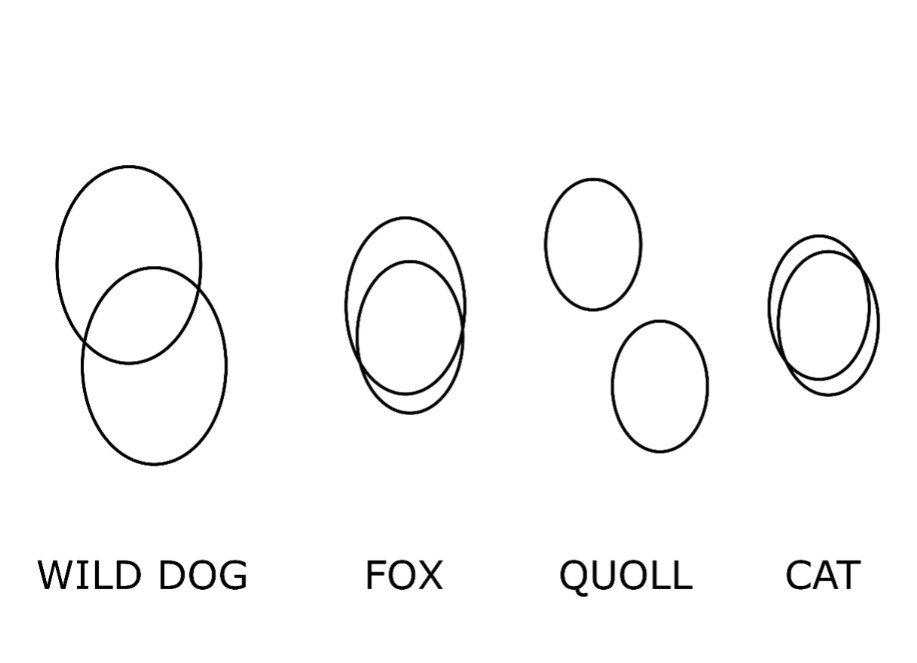

- Footprints. Fox prints can be easily distinguished from those of dogs or other predators – a fox’s pads can be separated by a straight line. Look for footprints around water, road junctions, animal trails, in holes under fences and on sandy or newly graded tracks.

- Fox scats. Look in similar location to footprints. Scats/faeces usually include hair, bones, feathers or insects.

- Livestock or wildlife kills or damage. PestSmart can help determine the cause of lamb deaths.

- Unexpected losses of lambs, kid goats or poultry.

Fox footprint size and shape relative to wild dog, quoll and cat prints. Not to scale. Adapted from Triggs 2004.

Usual fox footprint placement compared to wild dog, quoll and cat placements. Not to scale. Adapted from Triggs 2004.

Monitoring

Undertake monitoring before, during and after feral animal management activities. This will allow you to determine if your program is achieving its goals, or if you need to modify it.

The type of monitoring you do depends on how much information you need and the resources available. Monitoring can range from simple track counts, to camera trap tracking, to complex modelling.

Learn more about using monitoring as part of your fox management.

Motion cameras are a valuable monitoring tool for both foxes and wildlife. Photo: Rita Everitt

Humane fox control

When deciding which tool or technique to use, consider the consequences the tool might have on off-target animals, and consider the relative humaneness of the tool for both foxes and other species.

The tool or technique needs to be effective, humane, and suitable for the situation. An example of this is a well-planned, coordinated, and targeted fox baiting program is more effective at reducing fox numbers than just using padded-jaw or cage traps for landscape scale management. This is because setting and monitoring traps on a large scale is very time consuming and access is often limited. Bait type and methodology are designed to reduce impacts to off-target species and both 1080 and PAPP break down in the environment.

Be guided by the National Code of Practice for the Humane Control of Foxes and the associated Standard Operating Procedures. This code and operating procedures, along with an assessment of the humaneness of any fox control method, ensures that only the most appropriate and methods of control are used in fox management.

Effective control is more than just about removing foxes. The average number of foxes needed to be removed each year to stop population growth is 65% depending on conditions and birth rates. You need to remove more than the number of cubs being born and surviving to be effective.

Effective fox management needs to be about reducing impacts to biodiversity, health and/or agriulture not just reducing their numbers or distribution. Outcomes could include theatened species recovery or improved lambing success.

Learn more about ensuring the humaneness of fox control in Australia.

Coordinated, well-planned, landscape-scale baiting programs are an effective and relatively humane technique as part of a fox management program. Photo: National Wild Dog Action Plan.

Fox management tools

Effective fox control programs rely on using as many tools as possible in a coordinated and integrated way across a broad area. Because foxes have a high reproduction rate and are known to be able to travel long distances, ongoing management is vital to keep populations low, reduce chances of re-invasion and keep impacts to an acceptable level.

Managing foxes typically has one of two goals: to eradicate them from an area or to reduce their damage to an acceptable level.

Foxes can be eradicated if an area can be effectively sectioned off from the wider environment, for example on islands and in feral-proof fenced areas. Ongoing monitoring is needed after a successful eradication to ensure foxes have not re-invaded and are managed if they do.

If an area cannot be separated from its surrounding environment, the chances of maintaining the area without foxes are slim. In these areas, your management program needs to be long-term and should try to reduce damage as much as possible.

There are a range of tools available that can help you to control fox populations and manage their impacts.

Baiting

Poison baiting is the cheapest, most effective and environmentally responsible (CISS video, 2:19 min) broadscale fox control method currently available.

Successful baiting programs involve strategically placing toxic baits to attract and eliminate foxes.

There are two main toxins approved for fox control in Australia: sodium fluoroacetate (1080) and para-aminopropiophenone (PAPP). To access 1080 or PAPP, you will need to be trained and authorised, and licences and permits may be needed. Check the current rules with your state or territory agency.

There are two main ways to deliver toxic baits for foxes: laying ground baits and aerial baiting. Canid pest ejectors (CPEs) are another toxin delivery method for foxes.

Ground baiting is most common and involves laying and regularly monitoring buried or surface laid baits. A CPE is a spring-loaded mechanical device that ejects the toxin into the mouth of the fox when it is activated. Baits and CPEs are usually laid along tracks and roads. Aerial baiting is used in broader, usually more remote and sparsely populated areas and requires a special permit.

Baiting is one of the most effective invasive animal control tools available. It is cost effective and less time consuming than other methods and large areas can be covered so it can be scaled according to need. Baiting targets animal feeding behaviour and is best foxes are most active and/or hungry.

Learn more about using baiting for fox management in Australia.

Trapping

Trapping uses padded-jaw or cage traps to capture individual foxes so they can be removed from an area.

Trapping is labour-intensive and is therefore harder to apply at large scales. However, trapping is accessible to most people, and when undertaken by a trained individual it can be effective at targeting certain animals or places.

Using trapping, together with baiting and shooting, is more likely to successfully remove foxes that are not attracted to baits. A variety of trap types are approved for use.

Check with your state or territory agency for any regulatory requirements.

Learn more about using trapping for fox management in Australia.

Shooting

Ground shooting alone is not an effective method of controlling foxes, but is an important part of an integrated fox management program.

Shooting is highly labour intensive, making it difficult to apply at a large scale. It is an excellent tool for targeting small areas or problem animals that are not able to be eradicated by other forms of control. The effectiveness of shooting can be improved by using thermal technology.

Check with your state or territory agency for appropriate licences and permits.

Learn more about using firearms for fox management in Australia.

Exclusion fencing

Specially designed exclusion fencing can be used to keep foxes and cats out of an area, followed by removing any foxes or cats that are inside the fenced area.

Best practice involves a variety of eradication tools outside the fenced area to create a buffer zone with reduced predator numbers to help prevent fox incursions.

Exclusion fencing is a powerful tool when used to protect specific assets such as threatened species, livestock or infrastructure. But it is expensive to build and maintain, and has some disadvantages for wildlife behaviour and movement in the area as well as genetic diversity of animals inside the fence.

Learn more about using exclusion fencing for fox management in Australia.

Guardian animals

Guardian animals, often dogs, live with ‘their’ stock and protect them from anything they perceive as a threat. In Australia, guardian animals usually protect sheep, goats and poultry from wild dogs and foxes.

More research is needed to assess the value of guardian animals for protecting wildlife, however, because they could negatively affect the native species they are meant to protect.

Using guardian animals may not be appropriate for all circumstances. The best results usually come using guardian animals on small holdings as part of an integrated management plan.

Learn more about using guardian animals for fox management in Australia.

Den fumigation

Den fumigation floods a fox den with fatal concentrations of carbon monoxide to humanely euthanise any adult foxes or cubs in the den.

It is an effective tool for decreasing localised fox populations, especially in urban and peri-urban areas where other forms of control are limited.

However, on its own, den fumigation is not effective as a large-scale strategy due to its labour-intensiveness and seasonal restrictiveness.

Check with your state or territory agency for any regulatory requirements.

Learn more about using den fumigation for fox management in Australia.

Habitat management

Habitat management involves removing suitable habitat for foxes, which can reduce their population, or improving habitat for native wildlife to increase their chance of avoiding predation.

Habitat management can be a useful tool for managing foxes and their impacts in urban and peri-urban areas where fewer tools are available. It is also a useful tool in rural and native landscapes, as part of an integrated management program.

Habitat management can disrupt foxes’ access to food – you can remove carcasses and roadkill; lock away pet food; pick up fallen fruit; and secure bins, tips and composts. Clearing away waste, such as building materials and car bodies, and weeds that can be used for shelter and dens is also effective.

Restoring or conserving natural environments can reduce the impacts of foxes by providing greater shelter for wildlife, protecting them from predation. Native animals that commonly feature in fox diets tend to be found in open habitats, so providing dense sheltering habitat can reduce foxes’ ability to hunt them.

Habitat management can also work in urban parks and gardens; it can include revegetating, weeding, undertaking fire management and improving grazing regimes.

Learn more about using habitat management for fox management in Australia.

Rabbit control

Effectively controlling rabbits can indirectly reduce fox populations and increase the success of other control techniques such as baiting in places where rabbits form the major part of the fox diet and there is limited other food sources, such as in arid and semi-arid areas where foxes and feral cats have removed all other prey species.

In these situations, reducing rabbit numbers, particularly when they are abundant, can reduce fox numbers as they lose a major food source. A sudden loss of prey also increases the likelihood of a hungry fox picking up a bait.

However, foxes may switch to another prey species, which may cause short-term drops in prey populations, so take care if susceptible populations of threatened species with small populations are in the area.

Rabbit control is not likely to be effective where other prey is abundant such as coastal and temperate parts of Australia.

Research has shown that over the long term, native species respond positively after rabbit control that has led to reduced numbers of foxes. For the best outcomes, manage rabbits and foxes together.

Environmental monitoring is also important to determine the effectiveness of the rabbit control part of any program.

Learn more about using rabbit control for fox management in Australia.

Banner Photo: Barney Enders

Padded-jaw leghold traps are an effective tool for trapping foxes in targeted areas. Photo: Tony Buckmaster.

Canid pest ejectors are an alternative toxin delivery method designed to target foxes (and wild dogs). Photo: James Speed.