Feral cats (Felis catus) are a highly successful invasive pest in Australia and are one of the most threatening invasive alien species worldwide and are listed in the World Conservation Union’s list of the 100 worst invasive species. Feral cats are the same species as pet cats but defined differently based on how and where they live.

Cats arrived in Australia with European settlement. With the spread of farming across the country, cats were intentionally released into the wild to help control rabbits and rodents. Cats spread rapidly across Australia with European settlement. Historical records and genetic analyses show cats had colonised the entire continent within 70 years. Feral cats occupy 99% of Australia, including many of our offshore islands. The current overall estimate of Australia’s feral cat population is between 1.4 million and 5.6 million depending on climatic conditions. A further 0.7 million stray cats live in urban areas and there are at least 5.3 million pet cats (70% of which are allowed to roam and hunt).

Feral cats have few natural predators in Australia, and pose a threat to native wildlife, agricultural industries and human health.

Cats are ambush predators and carnivores, needing to eat meat to stay alive as they cannot digest plant carbohydrates. Feral cats prefer to hunt than eat carrion and will go after anything smaller than themselves. Flesh from their prey also provides them with most of the moisture they require so they can survive with limited access to water.

In Australia, cats mainly hunt small- to medium-sized native and exotic mammals, birds, lizards and insects. Cats also carry diseases that can affect humans and other animals. It is estimated that cats eat, on average, between 200–300 g per day.

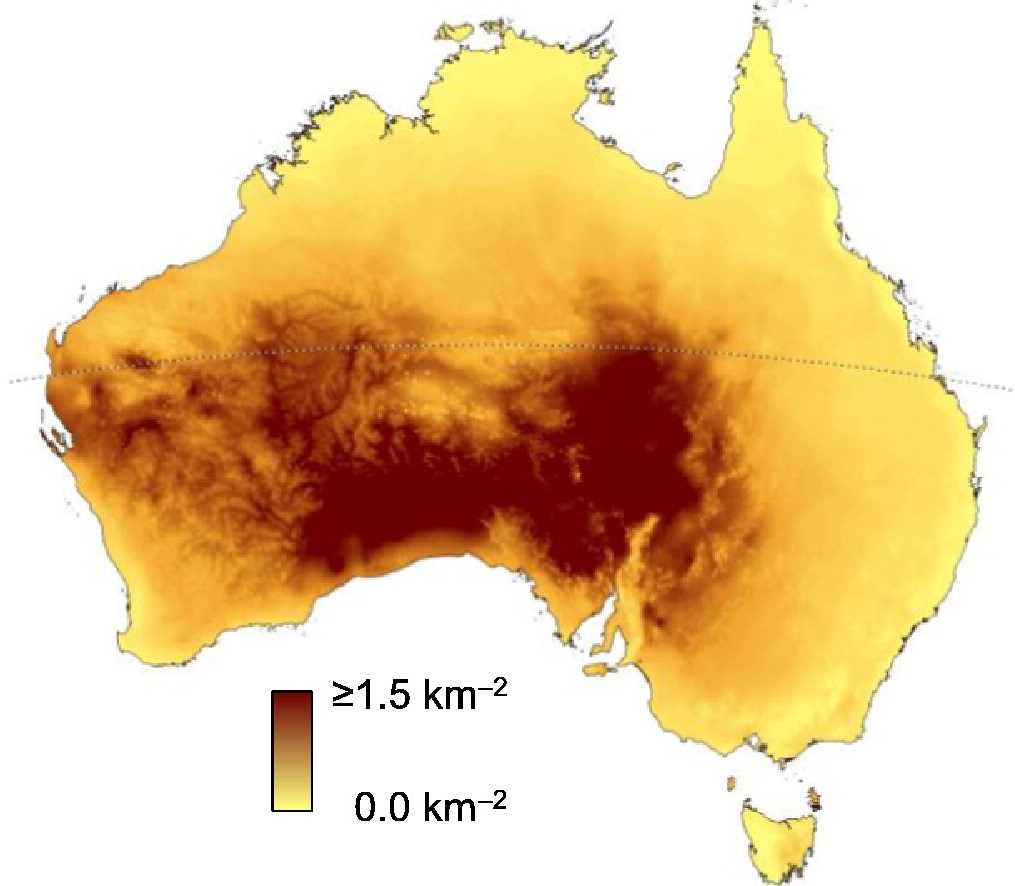

Feral cats are generally nocturnal. They can potentially produce up to three litters a year (~65 days gestation) averaging four kittens per litter. This means that they have the ability to reach high densities or re-populate an area very quickly when food is abundant. Social spacing and home ranges depend on food availability. Where there is more food, there are more cats and their home ranges are likely to overlap. Where food is scarce, such as dry arid areas, feral cats can become semi-nomadic, travelling greater distances to find resources.

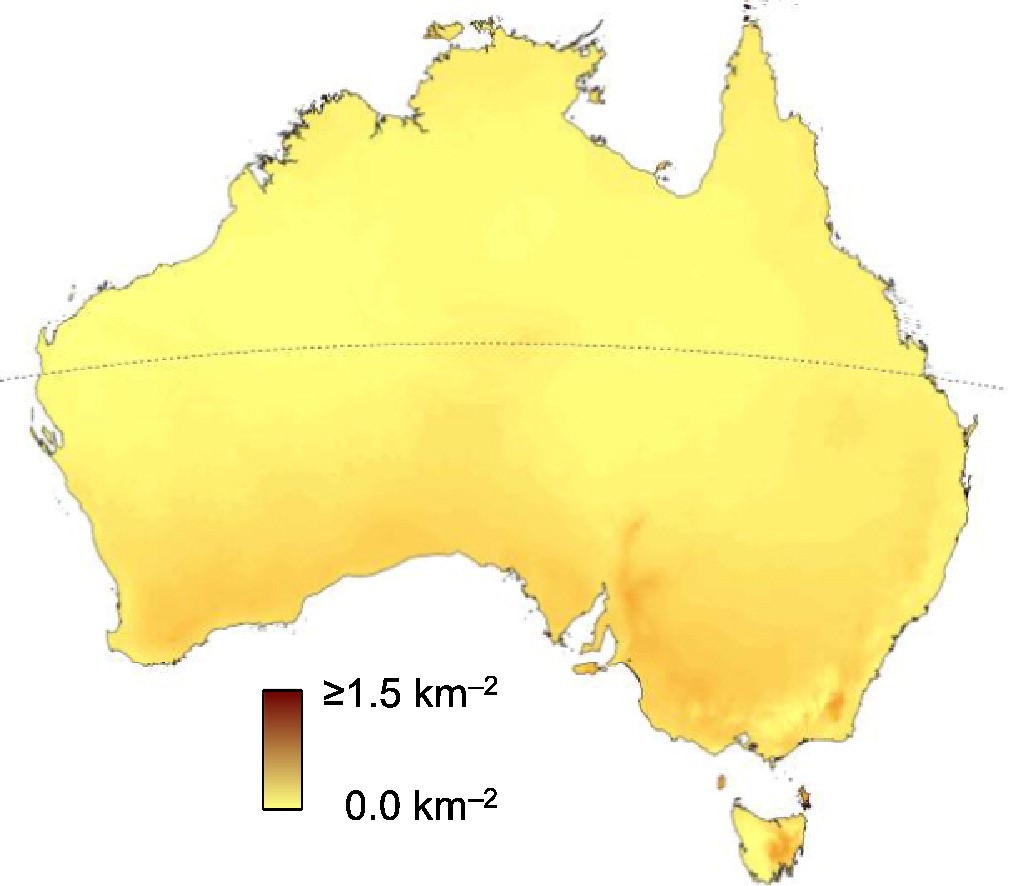

Feral cat denisities vary across the continent. Furthermore, densities in more arid areas can vary drematically depending unpon climatic and other conditions. The estimated mean density in natural areas is 1 cat per 4 km2 (ranging between 0.18 cats per 1 km2 in low rainfall years to 0.73 cats per 1 km2 in good rainfall years). They usually reach even higher densities on small islands or in human-modified habitats such as farms and rubbish tips. However, most of the time they are found in low numbers with relatively large home ranges, which can exceed 10 km2.

The average density of feral cats in these highly modified landscapes is 8.2 cats per km2.

Feral cats live, hunt and reproduce in the wild.

Photo: Nick Walker.

The density of feral cats in the bush fluctuates depending on weather conditions, increasing strongly after widespread rain across inland Australia which allows prey species to flourish. Model predictions during dry-average rainfall years (top) and wet-average rainfall years (bottom) (Legge et al. 2017).

Categories of cats

How we categorise cats is important for management. All cats, no matter how they are defined, prey on native fauna and can spread disease.

In Australia, cats are generally grouped into different categories based on where and how they live. The definitions of these categories vary widely across states and territories, organisations and materials. This has led to many approaches to defining cats, based on the level of ownership (e.g. owned, semi-owned, unowned), socialisation (e.g. socialised, semi-socialised, unsocialised), lifestyle (e.g. house cat, farm cat, stray, feral), and containment (e.g. indoor cat, free-roaming).

These categories do not always line up between jurisdictions or organisations. This can be confusing for people to understand their responsibility as pet cat owners or management options for those wanting to reduce impacts of cats. Getting greater clarity and alignment of category definitions will help understand responsibilities and management options.

Legislation in each state and territory, as well as local government, determines what can and cannot be done for managing cats, depending on what category they fall into: pet (sometimes referred to as domestic), stray or feral. It is important to find out what the definitions, requirements and restrictions are in your area before you start a cat management program.

The Threat abatement plan for predation by feral cats 2024 uses two categories: feral and pet, reflecting the difference in management needed, depending on the context and location, to protect native wildlife.

The National Feral Cat and Fox Management and Coordination program supports this binary categorisation of cats and would like to see this used more widely in both legislation and policy as well as education materials. For this website, we refer to: feral, stray (a subset of the feral cat category), and pet cats, as these are the terms most commonly used at the moment and consider their characteristics to be as follows:

- Feral cats live and reproduce in the wild in self-sustaining populations in natural habitats of all types and agricultural areas. They are not reliant on humans and survive exclusively by hunting and scavenging.

- Stray cats are often found in and around urban and peri-urban areas, industrial sites and rubbish tips. They are either in self-sustaining populations or become stray after neglect or irresponsible pet ownership. Some stray cats depend on food and water provided by humans. Stray cats are the most difficult to identify and can move between pet and feral cat populations.

- Pet cats live with and are generally dependent on humans for food and shelter. They are socially important and legally allowed in Australia. Most states have legislation about pet cat (sometimes defined as domestic cat) ownership but requirements vary for containment, registration, sterilisation and identification (i.e. microchips, collars). Responsible pet ownership, including containment, desexing and microchipping, can keep pets safe and reduce or eliminate the impact of pet cats on our environment.

Where not defined, assume that the term ‘cat’ on these webpages includes all three categories.

Feral cats find shelter where they can. Photo: John Carnemolla.

Pet cat safe and warm inside. Photo: Gillian Basnett.

Impact of feral cats

Feral cats are one of the most damaging invasive species to native wildlife in the country. Feral cats threaten Australia’s unique wildlife through predation, competition and the spread of disease, and impact livestock, particularly sheep, goats, pigs and poultry, through the spread of disease. Estimated costs to human health and agriculture is $6 billion a year.

By controlling feral cat populations, and stopping pet cats from roaming, it is possible to reduce these impacts.

Biodiversity impact

In Australia, at least 33 mammal species, excluding subspecies, have become extinct since European settlement. This is the highest rate of mammal extinctions in the world. Mammals are most common prey for all cats, with more than 1 billion mammals killed by cats in Australia every year.

Cats have played a key role in 26 of these 33 mammal extinctions, including two species of pig-footed bandicoot, the lesser bilby, the Nullarbor dwarf bettong, the desert rat-kangaroo and the broad-faced potoroo as well as native rodents including at least four species of hopping-mice, two species of rabbit rat, and the lesser stick-nest rat.

They also played a significant role in two of the nine bird extinctions and all three reptile extinctions.

Cats continue to drive population decline in Australian native animal species. Predation by cats is a recognised threat to over 200 nationally threatened species, and 37 listed migratory species (of which 9 are also listed as threatened).

In Australia, the greatest biodiversity impact is caused by feral cats living in the bush (68%). However, stray cats in towns and roaming pet cats also kill large numbers of animals. In fact, kills per km2 can be greater in towns because there is a higher density of cats.

- Feral cats eat about 1.5 billion reptiles, birds, frogs and mammals each year, and more than a billion invertebrates. A single feral cat eats, on average, 791 mammals, birds, reptiles and frogs and 371 invertebrates each year.

- A single stray cat eats, on average, 449 mammals, reptiles and birds per year.

- A single roaming pet cat eats, on average, 186 mammals, reptiles and birds a year, 110 of which are native. Pet cats that roam hunt and kill an additional 390 million mammals, birds and reptiles annually.

How vulnerable a native species is to this cat predation is highly variable, some species can co-exist with cats, others cannot. Many threatened mammals cannot survive even with low densities of cats. Those that are extremely cat-susceptible are now found only in small areas (islands and mainland fenced enclosures) where cats are absent. Identifying where native species fall along this continuum is critical for shaping the cat management actions necessary to prevent declines and extinctions. The background documents of the recent Threat Abatement Plan for Predation by Feral Cats 2024 provide useful information on native species susceptibility to predation.

The combined impacts of feral cats and foxes on biodiversity:

Feral cats and foxes hunt similar sized animals. This predation pressure has caused the extinction or population declines of a number of native species. However, the interactions between these two predators are complex and not always predictable. As an example, their predation pressure on some susceptible prey species is likely greater than the sum of their two parts but for other, less susceptible species, this is not the case. Strategic and targeted programs that manage predation of both invasive predators are likely to yield the best results.

Predation by feral cats and foxes combined, take a huge toll on native wildlife. Estimated number of animals killed in Australia each year by feral cats and foxes using an estimate average feral cat or fox density of 1 per 4 km2. Source: Stobo-Wilson et al. (2022). Note: feral cat and fox densities, and therefore their predation impacts, vary with different habitats and food availability.

Agricultural impact

Feral cats do not provide any economic value to Australia’s economy. In fact, feral cats have a significant environmental, agricultural and health cost.

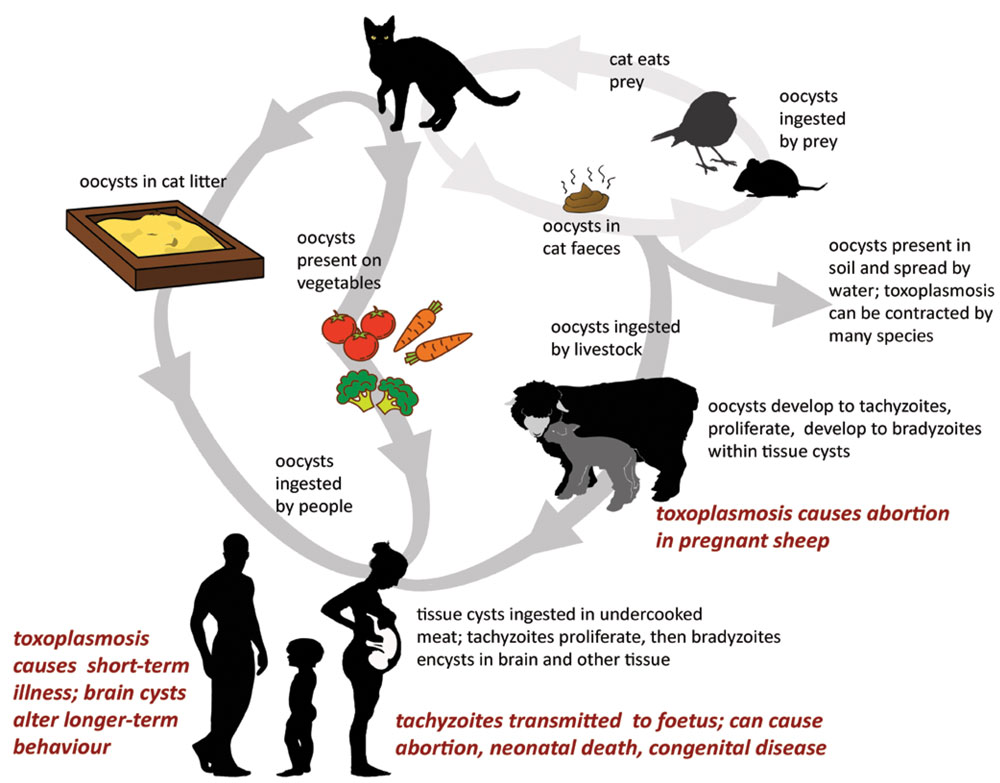

Feral cats carry and spread parasites that cause infectious diseases such as toxoplasmosis and sarcosporidiosis, which can be transmitted to native animals, domestic livestock and humans.

Recent studies have estimated annual losses of between $7.67 million and $18.3 million to the grazing industry due to cat-dependent parasites, with the sheep industry most heavily impacted.

Toxoplasmosis has been shown to be the cause of an average of 17% of sheep abortions in Australia. Impacts are likely to be higher in cool, wet climates because Toxoplasma gondii oosysts (like tiny eggs) survive longer in these environments. It can also cause abortions in goats, pigs and poultry.

Sarcocytosis, spread by cats, causes cysts to form in the muscles of sheep, making the meat unsellable. This meat either has to be trimmed or the carcass abandoned altogether. This cat-dependent disease costs the Australian sheep industry an estimated $5 million annually.

Lifecycle of Toxoplasma gondii. Source: Woinarski, J.C.Z., Legge, S.M., Dickman, C.R. 2019. Cats in Australia: Companion and Killer. CSIRO Publishing, p. 156.

Cultural, social and health impacts

Cats also impact our communities through nuisance behaviour and spreading disease. Some of the worst impacts from feral cats are the health implications for humans, through the spread of infections and diseases. Currently, cat-dependent diseases cost Australia $6 billion per year through health and agricultural impacts.

Many of the native species hunted and threatened by feral cats have important cultural significance to First Nations people in their stories, as totemic species and as food sources. Making sure these animals are known and seen by younger generations is important to First Nations communities.

Since their introduction to Australia, feral cats have been hunted for meat by First Nations people and in some communities are prized as both food and recognised as good medicine. They are also important companion pets for many.

Cats act as carriers of diseases transmitted to humans through bites, scratches, or contact with their bodily fluids and waste.

Cats can harbour bacterial infections that cause serious skin issues (pasteurellosis) and cat scratch fever (felinosis). Cats can also carry parasites that cause conditions such as scabies and toxoplasmosis. Toxoplasmosis poses a particular threat to pregnant women, potentially leading to miscarriages and congenital birth defects.

Feral cats, including strays, also play a significant role in injuring and transmitting various diseases to our pets, creating an increased burden on veterinary healthcare costs.

Feral cats also pose a significant risk as reservoirs for exotic diseases not yet present in Australia. In the event of an outbreak of diseases such as rabies or plague, feral cats have the potential to amplify health threats.

Feral cats hunt and kill animals up to their own body weight. Photo: H. A. Church.

Do you have feral cats?

With between 1.4 and 5.6 million feral cats spread across 99.9% of Australia, it is unsurprising to learn that feral cats are the single most damaging invasive species in the country.

Feral cats are often present but not seen, especially in areas with bushland where they can remain hidden during daylight. Their nocturnal lifestyle, combined with minimal vocalisations and avoidance of humans, makes it difficult to determine their presence.

The Glovebox guide for managing feral cats (PDF 1.4MB) and Planning guide for feral cat management in Australia (PDF 878KB) can help determine you have a feral cat problem.

Indicators of feral cats

- Sightings in your area. However, feral cats are not easy to see, so they may be around without you realising.

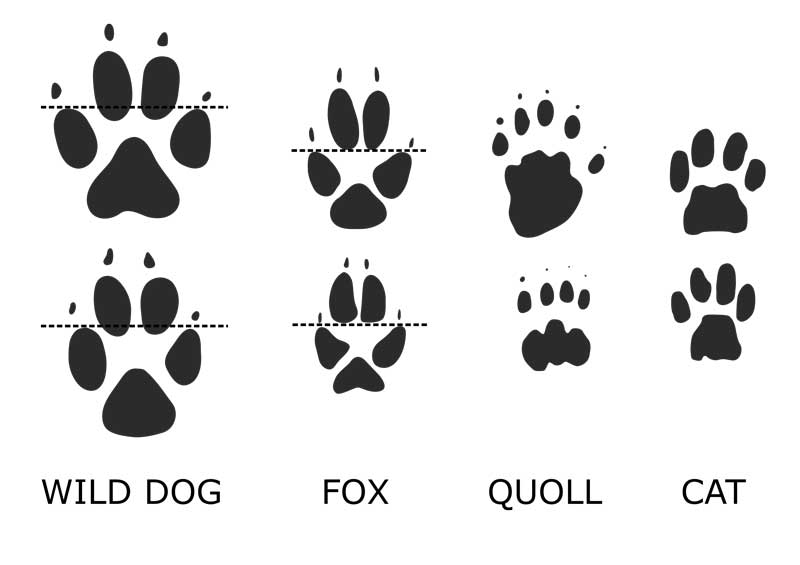

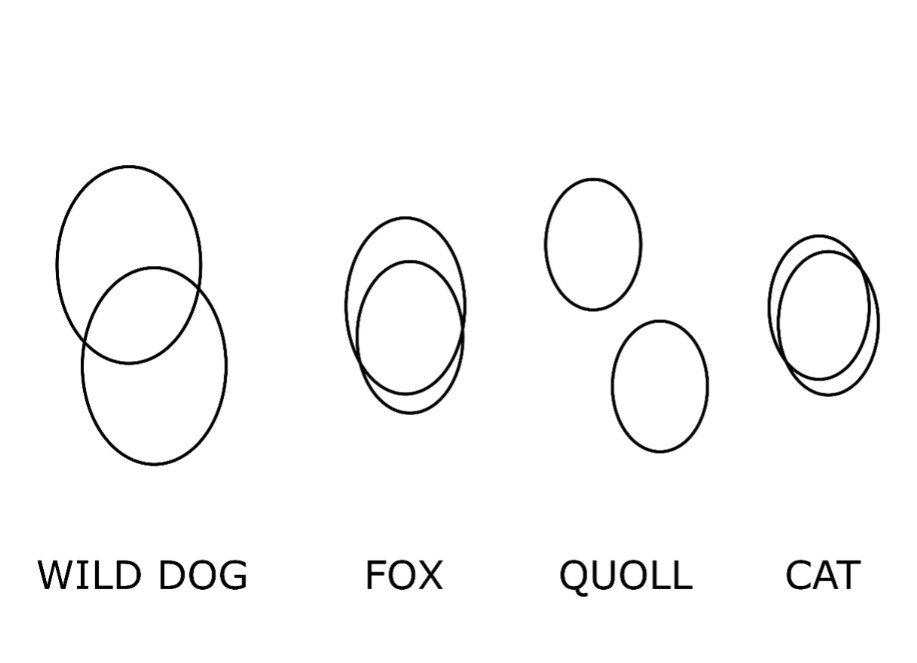

- Footprints. Cat prints can be easily distinguished from those of dogs, foxes or other predators. Look for footprints around water points, road junctions, animal trails, holes in fences, and on sandy or newly graded tracks.

- Cat scats/faeces. Feral cats are not like pet cats – they usually do not bury their scats.

- Livestock issues. If your sheep, goats, pigs or poultry have failed pregnancies, fewer young than expected, or have given birth to weak young, test for toxoplasmosis.

- Wildlife kills or other damage attributable to cats.

- Signs of illness in wildlife, particularly marsupials. Underweight, disoriented, reduced coordination, blindness, diarrhea, paralysis or breathing difficulties in wildlife may be signs of toxoplasmosis.

- Reported sarcocystis cysts at abattoirs.

Relative size and shape of wild dog, fox, quoll and cat prints. Not to scale. Adapted from Triggs 2004.

Usual footprint placement for wild dogs, foxes and cats. Not to scale. Adapted from Triggs 2004.

Monitoring

Undertake monitoring before, during and after feral animal management activities. This will allow you to determine if your program is achieving its goals, or if you need to modify it.

The type of monitoring you do depends on how much information you need and resources available. Monitoring can range from simple track counts, to camera-trap tracking, to more complex modelling. You should be monitoring both feral cats as well as the impacted wildlife or livestock.

Learn more about using monitoring as part of your cat management.

Responsible pet ownership

Owning a pet is a responsibility, not a right. By being a responsible cat owner you can protect your pet cat, be a good neighbour and look after wildlife.

Responsible ownership means desexing your cat, identifying it with a microchip as well as a collar and keeping it safely contained to your property to prevent it from roaming. Research shows that keeping your pet cat safe at home helps it live a longer, healthier and happier life.

Each state or territory and your local government will have requirements around pet cat ownership. To protect your pet, you might need to do more than is required by law.

Learn more about responsible pet ownership.

Motion cameras are a valuable monitoring tool for both feral cats and wildlife. Photo: CISS, NFCFMC Program.

Humane feral cat control

When deciding which tool or technique to use to manage feral cats, consider the consequences the tool might have on off-target animals, and consider the relative humaneness of the tool for both feral cats and other species.

The tool or technique needs to be effective, humane and suitable for the situation. For example, cage traps are not suitable for landscape-scale management because feral cats are less likely to go into a cage, and setting and monitoring cage traps on a large scale is very time consuming and access is often limited.

Be guided by the National Code of Practice for the Humane Control of Feral Cats and the associated Standard Operating Procedures. These codes and procedures, along with an assessment of the humaneness of any cat control method, ensures that only the most appropriate methods of control are used in feral cat management.

Effective control is more than just about removing feral cats. The average number of feral cats that need to be removed each year to stop population growth is 57% with a range of 24%–93%, depending on conditions and birth rates. You need to remove more than the numbers of kittens being born and surviving each year for a program to be effective.

Effective feral cat management needs to be about reducing impacts to biodiversity, health and/or agriulture not just reducing their numbers or distribution. Outcomes could include theatened species recovery or improved lambing success.

Learn more about ensuring the humaneness of feral cat control in Australia.

Standard operating procedures ensure management techniques are done in the most effective and humane way. Photo: Judy Dunlop.

Feral cat management tools

Effective feral cat control programs rely on using as many tools as possible in a coordinated and integrated way across a broad area. Because feral cats have a high reproduction rate and are known to be able to roam long distances, ongoing management is vital to keep populations low, reduce chances of re-invasion and keep impacts to an acceptable level.

Managing feral cats typically has one of two goals: to eradicate them from an area or to reduce their damage to an acceptable level.

Feral cats can be eradicated if an area can be effectively sectioned off from the wider environment, for example on islands and in feral-proof fenced areas. Ongoing monitoring is needed after a successful eradication to ensure feral cats have not re-invaded.

If an area cannot be separated from its surrounding environment, the chances of maintaining the area without feral cats are slim. In these areas, your management program needs to be long term and should try to reduce damage as much as possible.

There are a range of tools available that can help you to control cat populations and manage their impacts. Note: not all feral cat management tools are available in every state and territory or land tenure.

Baiting

Toxic baiting is the only method for directly controlling feral cats at a landscape scale in many areas.

Successful baiting programs involve strategically placing toxic baits to attract and eliminate feral cats.

There are two main toxins approved for feral cat control in Australia: sodium fluoroacetate (1080) and para-aminopropiophenone (PAPP). To access 1080 or PAPP, you need to be trained and authorised, and licences and permits are required. Check the current rules with your state or territory agency.

There are two main ways to deliver toxic baits: laying ground baits and aerial baiting.

Ground baiting involves laying surface baits, usually along tracks and roads under vegetation. Aerial baiting is used in broader, usually more remote and sparsely populated areas.

Baiting is one of the most effective invasive animal control tools available. It is cost effective and less time consuming than other methods and large areas can be covered.

Trapping

Trapping usually uses padded-jaw or cage traps to capture individual feral cats so they can be removed from an area.

Trapping is labour intensive and is therefore costly and harder to apply at large scales. However, with the right training, trapping is relatively simple, easy to do and accessible to most people. A variety of trap types are approved for use.

Systems to monitor traps remotely have been developed, improving animal wealfare and reducing the labour and cost of trapping programs.

Check your state or territory agency for appropriate licences, permits and requirements.

Shooting

Shooting is an increasingly common method of feral cat control in Australia, and is frequently used by land managers to try reduce feral cat populations in a targeted manner.

Shooting is highly labour intensive, making it difficult to apply at a large scale and it is unlikely to be an effective method on its own. It is an excellent tool for targeting small areas or problem animals that are not eradicated by other forms of control.

The effectiveness of shooting can be improved by using thermal technology.

Check your state or territory agency for appropriate licences, permits and requirements.

Felixer grooming traps

Felixer grooming traps are an innovative tool that target feral cats using automated target recognition and toxin delivery.

Felixers are relatively expensive to prepay long-term leases and are not currently suitable for landscape scale control. They are best suited for targeted feral cat control at specific locations.

Felixers use sensors to accurately identify and target feral cats, minimising impacts on off-target animals. On detecting a feral cat, the Felixer dispenses a precise dose of toxic 1080 gel onto the feral cat’s body, which it then ingests during grooming. This method uses the feral cat’s natural grooming behaviour to effectively deliver the toxin.

Felixers are solar-powered and with up to 20 cartridges (only 10 cartridges allowed on the label) so the unit can target multiple cats without needing attention.

Pet cats can be detected and impacted, so care must be taken to ensure Felixers are not placed in an area where a pet cat could trigger the unit. Pets can also be safeguarded by wearing bluetooth tags that deactivate Felixers

To access 1080, you need to be trained and authorised, and licences and permits are needed. Check the current rules with your state or territory agency. The Felixer training packege must be completed before cartridges are provided.

Learn more about using Felixer grooming traps to manage feral cats.

Exclusion fencing

Specially designed exclusion fencing can be used to keep cats out of an area, followed by removing any cats that are inside the fenced area.

Exclusion fencing is a powerful tool when used to protect specific assets such as threatened species or livestock. But it is expensive to build and maintain, and has some disadvantages for wildlife behaviour, movement and the genetic diversity inside the fence.

It is best practice to use a variety of other feral cat management tools outside the fenced area to create a buffer zone to help prevent cat incursions.

Learn more about using exclusion fencing to manage feral cats.

Indigenous hunting

Feral cats have greatly affected Australia’s First Nations communities, especially through their impact on culturally significant native species.

In some areas, First Nations people hunt feral cats to protect native wildlife, particularly species of important cultural significance. Feral cats are also hunted for meat as it is a valued food source and has perceived health benefits.

Indigenous hunting is undertaken in some First Nations communities and involves incredible skills in tracking and understanding of feral cat behaviour, and can be an effective way of managing feral cats in targeted areas.

Learn more about using Indigenous hunting to manage feral cats.

Habitat management

Habitat management involves removing suitable habitat for feral cats, which can reduce their population, or improving habitat for native wildlife to increase their chance of avoiding predation.

Habitat management can be a useful tool for managing feral cats and their impacts in urban and peri-urban areas where fewer tools are available. It is also a useful tool in rural and native landscapes, as part of an integrated management program.

Removing access to food can reduce cat numbers, particularly in urban areas – you can remove carcasses and roadkill; lock away pet food; and secure bins, tips and composts. Clearing away waste, such as building materials and car bodies, and weeds that can be used for shelter is also effective.

Restoring or conserving natural environments can reduce the impacts of cats by providing greater shelter for wildlife, protecting them from predation. Providing dense sheltering habitat can reduce a cat’s ability to hunt.

Habitat management can include revegetating, weeding, undertaking fire management and improving grazing regimes.

Learn more about using habitat management to reduce feral cat impacts.

Rabbit control

Effectively controlling rabbits can indirectly reduce feral cat populations and increase the success of other control techniques in places where rabbits form the major part of the feral cats diet and there is limited other food sources, such as in arid and semi-arid areas where feral cats and foxes have removed all other prey species.

In these situations, reducing rabbit numbers, particularly when they are abundant, can reduce feral cat numbers as they lose a major food source. A sudden loss of prey also increases the likelihood of a hungry feral cat picking up a bait or going into a trap.

However, feral cats may switch to another prey species, which may cause short-term drops in prey populations, so take care if susceptible populations of threatened species with small populations are in the area.

Rabbit control is not likely to be effective where other prey is abundant such as Tasmania and many coastal and temperate parts of Australia.

Research has shown that over the long term, native species respond positively after rabbit control that has led to reduced numbers of feral cats. For the best outcomes, manage rabbits, feral cats and even foxes together.

Environmental monitoring is also important to determine the effectiveness of the rabbit control part of any program.

Banner Photo: Leigh Deutscher

Felixer grooming traps are a new, innovative, feral cat management tool. Photo: CISS, NFCFMC Program.

Padded-jaw leghold traps are an effective tool for trapping feral cats and reducing off target captures. Photo: Judy Dunlop.